A violin student holding a Bow Hold Buddies device invented by Ruth Brons.

Source: Things 4 Strings

When Ruth Brons has a break between teaching her students in New Jersey how to play the violin, she's trying to find new ways to defend her small business against counterfeiters thousands of miles away in China.

Brons, 60, became an entrepreneur a decade ago when she invented an accessory that helps students hold the violin bow correctly. It can take years of painstaking lessons to learn the right technique. Brons said that with her invention, students can hold the bow correctly from their first lesson.

Trademarked as Bow Hold Buddies, she patented her invention in the U.S., Canada, Mexico, Europe and Australia. But as her business grew, Brons realized she needed to crack the Chinese market, where interest in Western classical music is exploding.

"China is where it's happening," Brons said. "There's a rising middle class and every parent wants their child to learn a Western classical musical instrument to elevate them in society."

When Brons hired an agent in 2013 to distribute her product from Beijing, they discovered there was indeed a demand in China – the problem is that they weren't the ones supplying it.

'It's like whack-a-mole'

Brons and her agent Jerrie Zhao found counterfeit versions of her product already for sale on the e-commerce site Taobao. They discovered that two factories – one in the major port city of Ningbo and the other in Hengshui – were manufacturing the knockoffs, Zhao said. The counterfeits were being sold at a fraction of Brons' price.

Even worse, the patent Brons paid about $100,000 for in the U.S. had been copied. Counterfeiters had translated all 32 claims of her patent into Mandarin and registered it in China, she said.

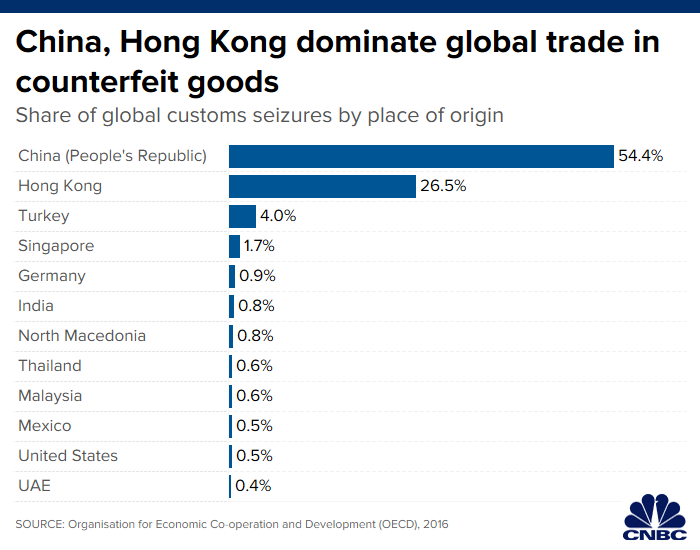

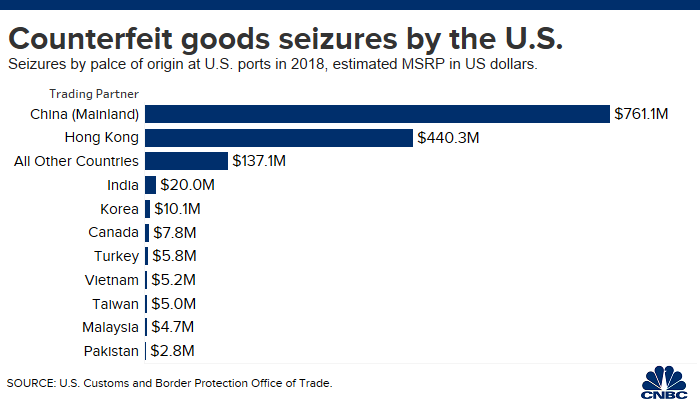

Intellectual property theft is a pervasive issue in China and a central bone of contention in the U.S.-China trade war. In 2018, 87% of all counterfeit products seized at U.S. ports came from mainland China or Hong Kong, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection's Office of Trade. It's not just a problem for the U.S. Eighty percent of all counterfeit products seized worldwide originated in China, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

While the discussion about protecting intellectual property has largely focused on big tech companies, small-business owners like Brons are fighting an uphill battle with limited resources to protect their patents and trademarks – the core of their business – in China's legal system.

Brons, through her legal representation, went to court twice in China to have the copied patents invalidated, a process that she said took years. It has cost her business tens of thousands of dollars to invalidate the patents and get listings of fake products taken down from Taobao, Brons said, but new counterfeit products keep surfacing.

"You take down one and another pops up," Brons said. "It's like whack-a-mole."

She says the annual revenue of her business, Things 4 Strings, has plateaued at around $320,000 because the fakes are hampering growth in China, which should be her most important market. And as the legal bills pile up, she has less money to invest in her business on important expenditures like advertising.

"I'm to the point where I need to write my senator," Brons said. "The legal avenues to get the knockoffs seems to be a coffer raider without a whole lot of results."

The counterfeit products also surface on U.S. e-commerce sites like Amazon and eBay, Brons said.

In April, the Trump administration warned Alibaba, Amazon, eBay and other e-commerce sites that the U.S. government would pursue a regulatory crackdown if the sites did not do more to fight the sale of counterfeit products. All three sites said they were committed to working with the U.S. government to combat fake products.

Lax enforcement

The problem with intellectual property theft in China is not due to a lack of legislation, according to Fred Rocafort, a former U.S. diplomat who has worked on IP issues in Asia for more than a decade. The domestic legal framework is adequate in China, Rocafort said, and Beijing is a signatory to several international agreements on intellectual property.

"The problem emerges when you start looking at the enforcement, which takes place at the more local levels than at the national level," said Rocafort, now an attorney at the international law firm Harris Bricken. "There's a corresponding loss of enthusiasm for enforcement as you move down the chain."

Combine the lax enforcement with the fact that China is the world's manufacturing powerhouse, and the result is a pervasive problem with counterfeiting and intellectual property theft. Despite the challenges, Rocafort said American businesses can have success protecting their intellectual property by working within the Chinese system.

First and foremost, you have to register your intellectual property in China to have any chance of protecting it there, Rocafort said. This is where Brons' problem started.

She decided against patenting her invention in China when she was starting her business. At the time, she didn't see the point. China seemed far away and she had heard the courts didn't really enforce U.S. intellectual property anyway. Brons expressed regret about her decision, but she said getting a patent in China was just too expensive for her at the time.

"I could not have afforded it," she said. "I'm just a violin teacher."

But the costs associated with not registering your intellectual property are also steep. Brons said she's spent at least $100,000 fighting counterfeiters in China, a substantial some of money for her small, family-owned business. She has since registered copyright protection in China to cover the design of her product, after hearing that Beijing was doing a better job of enforcing intellectual property rights.

China has indeed instituted reforms in recent years as Chinese President Xi Jinping has made public commitments to strengthening intellectual property protection, but the U.S. has said implementation has not been sufficient.

Washington and Beijing were reportedly making progress on the issue before trade talks collapsed in May and the trade war escalated with several new rounds of tariff increases. The U.S. accused China of backtracking on its commitments, which reportedly included strengthening its laws to protect intellectual property. Beijing denied that accusation.

U.S. and Chinese trade negotiators are set to meet this month in Washington, D.C., for another round of talks.

"A lot China's push to improve its IP enforcement is a result of outside pressure," Rocafort said. "Frankly, left to their own devices there would probably not be a lot of progress in terms of strengthening enforcement."

'This is like paying taxes'

To have success fighting counterfeiters, you have to be willing to cooperate with the Chinese authorities, Rocafort said. This requires doing a lot of the investigative legwork yourself, he added.

Larry Griffith has had some success in enforcing his intellectual property in China. He is president and CEO of Bohning Co., a small business in northern Michigan that generates about $6 million to $7 million a year in revenue from manufacturing parts for archery equipment.

Griffith knew for years that his company's trademarks were being infringed in China. He said his sales in Australia, one of his most important markets, dropped to less than $100,000 from $500,000 a year due to counterfeit products from China.

In response, he decided to apply for trademark protection in China, a process that took 14 months. He said Bohning has spent about $250,000 protecting its trademarks from counterfeiters in China and in other countries where the Chinese knockoffs surface.

With his trademark in hand, he hired the help of a law firm in Beijing that had a team of investigators. They identified four factories that were making counterfeit goods. Police conducted successful raids on three factories located in Ningbo. They were able to seize tens of thousands of dollars of counterfeit products in terms of the goods' estimated value in the U.S., Griffith said. None of this would have been possible without Chinese trademark protection, he added.

"The Chinese government upheld our rights," Griffith said. "It was not a matter of nationalism; it was a matter of law. And I think the Chinese are like a lot of countries -- they're very legally minded; they want to be fair."

Despite this success, the battle is far from over for Griffith. His company is still finding plants making counterfeits, and he says it will likely take years to work through them all. Anyone who plans to go after counterfeiters in China should expect a time-consuming, bureaucratic, tedious and expensive process, he said.

"I think this is like paying taxes – it's never going to go away," Griffith said. "But you can really damage it. I look at counterfeiters like a bully on a playground. If you stand up to them and give them hell, they're going to find an easier target."

0 Comments