Employees at Willson Electronics manufacturing facility in St. George, Utah.

Source: Wilson Electronics

Bruce Lancaster is confident his company can beat any competitor.

The problem, he says, is that Wilson Electronics is fighting an uphill battle against several Chinese companies that do not respect intellectual property laws and don't play by the rules.

"These Chinese competitors are using my IP and are not paying a royalty," says Lancaster, Wilson Electronics' president and CEO. He says the competitors' unfair and at times illegal business practices are costing Wilson millions of dollars, a double-digit percentage hit to its revenue.

It's a common complaint among companies that manufacture in the U.S.

While many American businesses are calling on the Trump administration to end the trade war against China, Wilson Electronics and other manufacturers say that tariffs, if they are targeted in scope, will help address longstanding unfair trade practices used by China.

"These tariffs are a very necessary evil," Lancaster says. "You've got to have something to start changing the behavior, and I believe that behavior is being changed."

'A blunt weapon'

Wilson Electronics makes cellphone signal boosters for consumers and businesses. Its devices strengthen the signal on your smartphone so your calls aren't dropped and your data doesn't slow down in places where reception is poor.

The luxury jeweler Tiffany and Co., for example, uses Wilson's products in its stores to keep customers connected while they are shopping.

Founded in 2000, Wilson has more than 300 employees in Salt Lake City and St. George, Utah, as well as Dallas, Texas. The company designs and assembles its products in the U.S.

A leader in its field, Wilson has dozens of patents and dozens more pending, Lancaster says. The FCC regulates the industry to make sure the devices don't amplify signals so much that they interfere with cell towers.

Lancaster says the cheapest way for Chinese competitors to meet FCC requirements and sell their products in the U.S. is by taking Wilson's intellectual property. Some competitors, he says, don't even bother meeting standards and just sell their products in the U.S. illegally online.

Employees at Willson Electronics manufacturing facility in St. George, Utah.

Source: Wilson Electronics

And these competitors often use aggressive pricing to undercut Wilson's sales, the company said in a letter to the U.S. Trade Representative.

Lancaster doesn't believe tariffs are good, he says. He calls them a blunt weapon and knows that they come with an economic cost — one that Wilson has experienced itself.

Wilson sources some components from China that are subject to Trump's tariffs. That means the company is paying a tax on those components, while the competition in China is not.

Lancaster, however, supports the administration's decision to put tariffs on a category of goods that includes Chinese-made cellphone signal boosters. This action, he believes, will help level the playing field for U.S. domestic manufacturers. He says he doesn't see another way to force the competition to play fairly.

Lancaster says he "did a bit of a happy dance" when he learned Chinese-made boosters were getting hit with a 25% tariff, which went into effect in May. In fact, he says the tariffs should be even stiffer.

"The tariffs mean we're going to win more market share, which allows us to grow even further," Lancaster says. "With growth we're going to be hiring more people and developing more technology."

.1568392020490.png)

'Being an American product does matter'

Spencer Gore believes in a trade policy that supports manufacturing high-tech goods in the United States.

A former battery engineer at Tesla, he left the company to found a start-up called Impossible Aerospace, which builds battery-powered electric drones.

These drones are made for police, fire departments and other first responders across the country that don't have the budget for a helicopter to survey emergency situations from the sky.

Impossible Aerospace's 30 employees design and manufacturer the drones in Santa Clara, California. Gore sees advantages to keeping production in the United States.

"Being an American product does matter to a lot of our customers, but more importantly our competition right now is against Chinese companies that are vertically integrated," he says.

Impossible Aerospace US-1

Impossible Aerospace

By keeping manufacturing in the U.S., Impossible Aerospace is more nimble than if the company were spread out across a 12-hour time zone difference, Gore says, which helps it keep up with competitors that are tightly integrated in China.

But it's still an uphill battle. The challenge, according to Gore, is that Chinese competitors can aggressively cut prices and undercut U.S. drone companies. He supports slapping tariffs on Chinese-made drones so competitors in China do not have an unfair advantage.

"I actually believe that there is some sense in applying strategic tariffs that are in the best interests of the United States," Gore says.

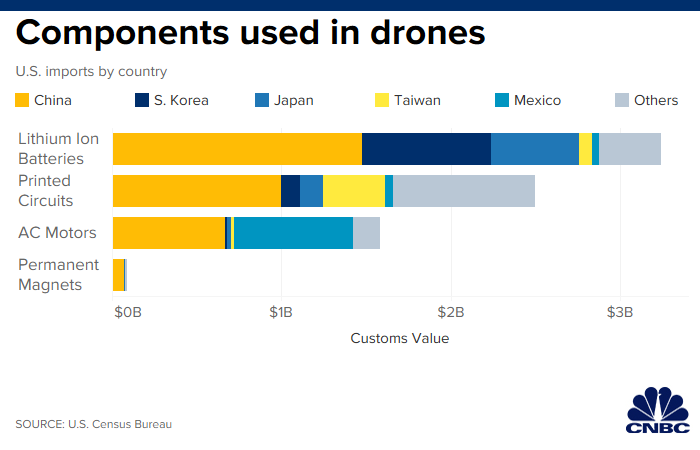

Impossible Aerospace pays tariffs on components it sources from China, such as lithium-ion batteries and AC motors. Gore says tariffs on Chinese-made drones should be higher than what he pays on the components.

A policy like this would help support American-made technology, he says, and create an incentive to keep manufacturing in the U.S., which would ultimately protect American intellectual property.

"What we're hoping for is a level playing field where American companies do not have an incentive to outsource jobs," Gore says.

'Something needs to be done'

Neil Muyskens says it's getting harder and harder to compete with manufacturers in China.

Muyskens is the founder and CEO of Unicomp, a company that designs and manufactures customized mechanical keyboards at its plant in Lexington, Kentucky.

Unicomp was always a small business, but times have gotten tough. The competition from China has significantly cut into the company's revenue, Muyskens says. At its peak, Unicomp had 120 employees. Today, it has 25 employees.

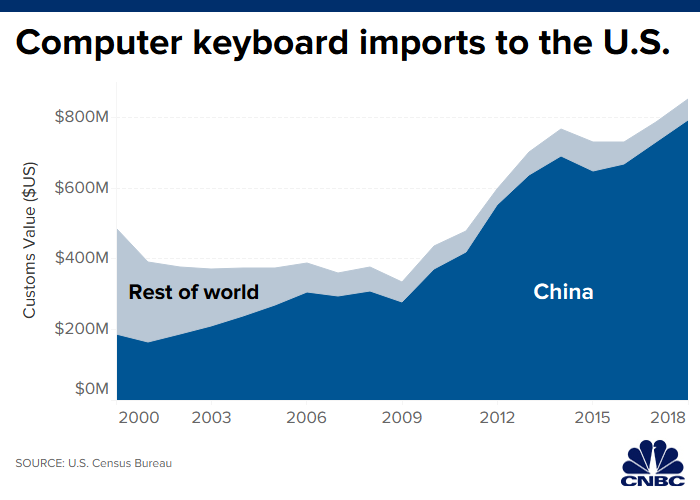

The challenge is that Unicomp makes a premium product — its mechanical keyboards cost about $90. Many companies, though, have switched to cheap keyboards made in China.

"We know we're competing against a low labor-cost business," Muyskens says of the competition in Asia. "We are at a significant cost disadvantage and always have been."

Muyskens is not an enthusiastic supporter of the Trump administration's tariffs. Unicomp sources some keyboard components from China that have been hit by import duties of 25%.

In response, Unicomp has raised prices where it can by about $5, which has reduced the company's volume. Muyskens says he can't just raise prices across the board to absorb the tariffs. That's because the prices for Unicomp's large commercial accounts are locked in place.

"I would just as soon as there be no tariffs whatsoever," Muyskens says. "But I'm also a realist and understand there are things that are wrong. U.S. manufacturers are at a disadvantage, and something needs to be done."

Muyskens asked the administration to remove tariffs on keyboard components and impose more targeted tariffs on finished Chinese-made keyboards to level the playing field. Keyboards from China will face 15% duties starting Dec. 15.

"At my core I'm a free-market guy," Muyskens says. "But it's not a free market."

0 Comments